European Telcos Sound Alarm Over Flagging Open RAN Progress

European telecom companies recently sounded an alarm that they may be falling behind the rest of the world in their efforts to develop open-interface radio access network (RAN) technologies. The technologies, called Open RAN and which would provide new ways to mix and match network components by “opening up” the interfaces between them, are widely believed to be an important opportunity to drive down the costs of network deployments and allow new players to enter a rigid market.

Five companies—Deutsche Telekom, Orange, Telecom Italia, Telefónica, and Vodafone—published a report outlining why they feel Europe as a whole is lagging behind other regions such as the U.S. and Japan in developing Open RAN. The companies point to both a lack of companies developing key components, notably silicon chips, for Open RAN technologies, as well as the need to get incumbent equipment vendors Ericsson and Nokia on board with Open RAN development. And there’s a deeper issue in that the exact definition of Open RAN is still in flux, allowing different companies to prioritize different technologies and proclaim that they fall under the banner of Open RAN.

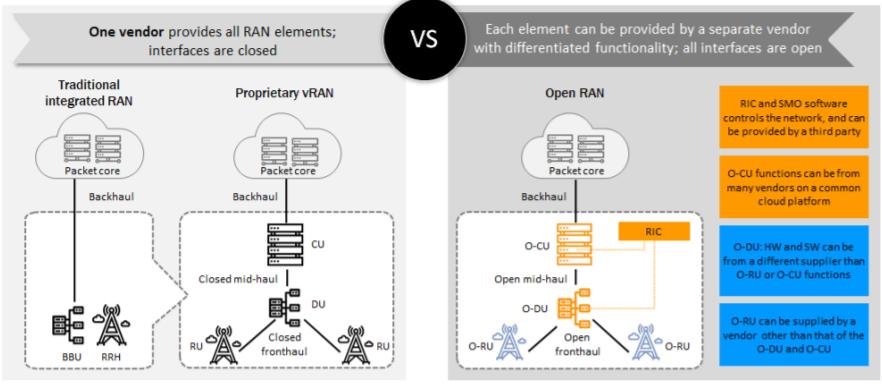

Briefly put, the cellular networks we use to send text messages and make calls have a few basic components. Cell towers receive analog signals via their antennas; radio units convert those signals to their corresponding digital versions; and then baseband units process the signals, correct errors, and route the digital signals to wherever they need to go. Traditionally, network operators like any of the five companies listed above purchase this equipment from a single vendor, be it Ericsson, Nokia, Samsung, or Huawei, to name the biggest players.

Vendors have an incentive to lock operators into their respective ecosystems by ensuring their components don’t work with components from their competitors. Frustrated by being in a captive market and the expenses associated with upgrading and rolling out networks, several operators created the O-RAN Alliance to force the development of standards and technologies that would lead to Open RAN implementation.

Olivier Simon, the Radio Innovation Director at Orange, says there are three aspects to Open RAN. The first is openness between the interfaces of different network components. The second is decoupling network software from hardware and moving more of a network’s operations into the cloud. And the third is increased intelligence: letting AI and machine learning techniques manage more of the network’s performance. “I think everyone agrees there are these three aspects,” says Simon, “but what becomes more tricky is that none of them are mandatory.”

For example, a recent report that calls out the difficulties in getting the Open RAN effort to coalesce around an established set of changes to the fundamentals of network architecture points out that Nokia has developed Open RAN software, but that its software runs only on Nokia’s hardware. Nokia’s developments do feature open component interfaces (the first issue addressed by Open RAN), but the operators authoring the report take issue with the lack of software-hardware decoupling in Nokia’s developments (the second of the three issues network carriers wish to tackle).

Nokia has pushed back on the report, explaining that its components are compliant with the O-RAN Alliance’s definitions for open interfaces. But that gets back to the issue at the core of Open RAN development: Do the three aspects have equal weight, and in what ways should they be prioritized and implemented? Nokia argues that its components are Open RAN-compliant because they have open interfaces. The operators that authored the report feel that’s not enough because the Nokia components don't adequately prioritize the other emerging aspects they say are critical to the success of the effort.

There is a sense from the operators that these kinds of back-and-forth arguments about what makes a particular component compliant are stymying Open RAN development in Europe. “It’s more an ecosystem question than a deep technical question,” says Simon. The network operators consider Ericsson and Nokia to be important parts of Europe’s telecom ecosystem because of their global dominance in supplying equipment. But there's a downside to having these telecom titans around, because it can be difficult for large incumbents in an industry to react swiftly to a new technology.

That has allowed U.S.-based companies like Mavenir and Parallel Wireless, and Japanese companies like Rakuten, to set the pace for Open RAN development, according to an email from Fransz Seiser, the Vice President of Access Disaggregation at Deutsche Telekom. That said, Rakuten (a Japanese network operator) has enlisted Nokia to develop and build its Open RAN network using equipment from multiple vendors, which Nokia points to as another piece of evidence that it is committed to Open RAN development.Still, it could be argued that the Rakuten-Nokia multi-vendor deployment, while prioritizing the open interface aspect, yet again fails to satisfactorily focus on the mission to decouple software and hardware). Seiser echoes Nokia's sense of things, insomuch as the company has demonstrated progress with its recent introduction of multi-vendor support.

Tanveer Saad, the Head of Edge Cloud Innovation and Ecosystems at Nokia, says that Nokia is taking a bigger responsibility as a “solution provider.” “We are actually building the solution with different components from our ecosystem players, so it can be a multi-vendor kind of environment.” On the one hand, Nokia has demonstrated a desire to ‘move quick’ in response to the disruption created by Open RAN by developing multi-vendor solutions like the one for Rakuten. On the other, the company seems to be hoping that it can maintain dominance as an end-to-end network provider, albeit by offering options with multiple vendors’ components instead of just their own.

Also driving the sense that Europe is falling behind is a lack of companies such as Broadcom, Intel, and Qualcomm producing silicon chips that will ultimately be integral to Open RAN's success. These chips will be vital for the development of AI that can manage networks. While the consensus is that this third aspect of Open RAN is the farthest in the future, the operators argue that Europe should begin investing in alternatives to existing chip manufacturers in order to shore up that weakness in the continent's network communications ecosystem.

Open RAN surprised some in the industry with how quickly it has risen to prominence. The O-RAN Alliance was founded in 2018 with just five members. It now has over 260 members. Cellular “generations” such as 4G and 5G typically exist on a ten-year cycle of research, standardization, and commercialization. Open RAN is moving much faster, and even despite the recent concerns about lagging behind—or perhaps because of them—there is still a sense in the industry that Open RAN will make a big impact in the coming years.