Biden wants local governments to provide broadband internet. Could they compete with Comcast and Verizon? Share Icon Facebook Logo Twitter Email Link Icon Email Twitter

The rural borough of Kutztown couldn’t convince companies to bring faster internet to its community. So the town, about 70 miles northwest of Philadelphia, built its own broadband network.

Since 2000, Kutztown’s 5,000 residents can buy internet service from a municipal entity, just like the water and electricity they purchase from borough utilities. The publicly-owned, fiber optic network has not only provided improved download speeds, but has also lowered prices, the town says. A private company has since slashed its rates to compete, it adds.

“Whether you subscribe to the service or not, you’re still benefiting from its existence,” said Mark Arnold, the borough’s telecommunications director.

President Joe Biden’s $2 trillion infrastructure plan aims to expand internet access by building more such community broadband networks. The Biden administration has called broadband “the new electricity,” noting the federal government worked to bring power to nearly every home under President Franklin Roosevelt because it was crucial to the economy.

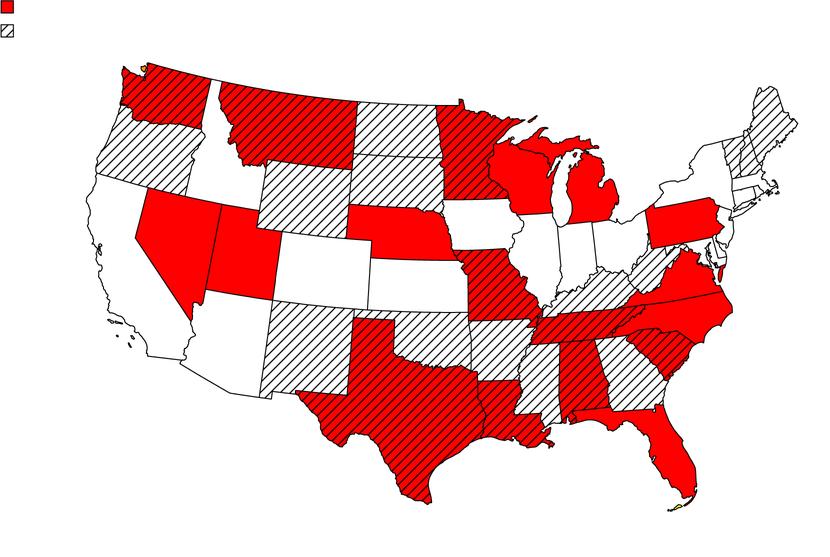

Biden’s internet proposal would override 19 state laws that restrict municipalities from competing with private providers, including a law in Pennsylvania that passed after Kutztown already built its network.

Biden’s plan has renewed debate over whether municipal broadband makes the internet more affordable and accessible. Advocates, including Democrats in Washington, argue that public networks give internet titans like Philadelphia-based Comcast Corp. and Verizon Communications Inc. much needed competition. That would drive down prices and create more options.

But critics, including Republican lawmakers and the cable industry, say the taxpayer-funded networks are unfair competition, discourage private investment, and are ill-equipped to keep pace with technology.

A University of Pennsylvania study found the public projects can be money-losing operations. And Philadelphia offers a cautionary tale about how municipal internet projects can fail.

The coronavirus crisis underscored the necessity for high-speed internet as governments closed schools and offices, forcing Americans to stay home. Cities such as Philadelphia scrambled to connect low income families that did not have computers or internet.

According to the Biden administration, over 30 million Americans live in areas without broadband infrastructure, and millions more can’t afford it because the U.S. has higher broadband prices than other countries.

At the same time, more than three-quarters (76%) of Americans believe that internet service is as important as water or electricity in today’s world, according to a February survey by Consumer Reports, a pro-consumer group.

‘Gig City’

Biden’s plan would spend $100 billion on broadband infrastructure, prioritizing support for networks run by local governments, cooperatives, and nonprofits. The president believes such networks have less pressure to turn profits and can commit to serving entire communities, an administration official said.

“Broadly speaking, I think what the president wants to do is encourage more competition,” said Bharat Ramamurti, deputy director of the National Economic Council. “There are a lot of parts in this country where there’s only one, maybe two internet providers in the area, which means that oftentimes the price is high or service isn’t as high quality as it should be.”

Chattanooga, Tenn., offers a broadband success story. The city’s electric power company deployed a fiber optic network a decade ago to deliver the internet and operate a smart grid.

The utility paid for the project with a $169 million bond issue and a $111 million grant from the Obama administration, which wanted to stimulate the economy after the Great Recession.

The city has been dubbed “Gig City” for offering gigabit (1,000 mbps) internet speeds. More recently, PCMagazine called the city something else: the best city to work from home, after the coronavirus forced consumers to work remotely.

The city-owned network has never raised its prices, claims to have the world’s fastest speeds, and has lured tech startups to the city. A recent study from the University of Tennessee said Chattnooga’s Hamilton County received $2.7 billion in economic benefits from the infrastructure, including business investments and residential bill savings.

The public network’s primary competitors are Comcast and AT&T Inc., and it’s winning the market share battle. It serves 116,000 customers out of about 170,000 homes and businesses in its footprint, according to J. Ed. Marston, head of marketing for the utility, EPB, formerly called the Electric Power Board of Chattanooga.

For $58 a month, EPB customers can get download and upload speeds of 300 megabits per second, far exceeding the Federal Communications Commission’s minimum broadband requirements. It also offers 1,000 mbps for $68 per month and 10,000 mbps for $300 per month, the latter plan it calls “the world’s fastest internet.”

“We have to charge enough for our services to make what we’re doing sustainable,” Marston said. “But we’re community based, so our focus is providing the best value, the best pricing that we can.”

‘Oversold solution’

Municipal broadband models widely vary. While Chattanooga’s system is city-owned, other towns have built then leased their infrastructure. Others have paid private firms to build and operate community networks.

In all, about 200 cities offer such citywide internet service, said Christopher Mitchell, director of the community broadband networks program at the Institute for Local Self Reliance, an advocacy group.

Although municipal broadband has worked in places such as Kutztown and Chattanooga, taxpayers can be on the hook if the expensive projects don’t work out.

Christopher Yoo, a University of Pennsylvania professor of law, communications, and computer science, studied the financial viability of 20 municipal fiber networks. He found that 11 of 20 didn’t make enough cash to cover operating costs, and just two were on track to pay off the total project costs during the 30- to 40-year useful life of the systems.

“Municipal broadband is often oversold as a solution,” Yoo said. “Taxpayers are sort of told this is something for nothing, that it’s going to make money for the city, and it’s not really portrayed as a potential burden.”

The cable industry criticized Biden’s broadband plan for prioritizing the public sector. Republican lawmakers have introduced their own proposals, including one that claims to promote competition by limiting government-run networks.

“The White House has elected to go big on broadband infrastructure, but it risks taking a serious wrong turn in discarding decades of successful policy by suggesting that the government is better suited than private-sector technologists to build and operate the internet,” said Michael Powell, president and CEO of the NCTA, also known as the Internet & Television Association.

Corporations such as Comcast have worked to close the digital divide with free and low-cost service.

The company offers a $10-per-month plan for low-income customers. In Philadelphia, the cable giant has partnered with the city to connect thousands of families with free home internet during the pandemic and has equipped 50 community centers with free WiFi, called “Lift Zones.”

But activists and elected officials note there are still gaps in the market, with people unable to access or afford an increasingly important internet connection. They argue community networks can help.

“People appreciate that this is not easy. It’s hard work. And it’s not for every city,” Mitchell said. “But it needs to be the cities that decide whether or not this is the right solution for them.”

Pennsylvania’s history with broadband

In 2004, Philadelphia planned to build the largest municipal WiFi grid in the country. The ambitious “Wireless Philadelphia” project drew worldwide acclaim and envisioned over 100,000 people, especially its poorest residents, connecting to low-cost internet.

But the endeavor failed four years later when Earthlink, the private company the city chose to build and run the network, pulled the plug after spending $17 million and signing up just 6,000 customers. Experts now say the wireless technology wasn’t ready for the moment and the city erred in handing ownership to a private firm to avoid spending tax dollars.

A lasting legacy of Philadelphia’s failed effort is a Pennsylvania law that limits municipal broadband. Sensing government competition, Verizon and other internet incumbents successfully lobbied lawmakers in 2004 to largely bar local governments from providing broadband. The law prohibits localities from offering broadband “for compensation” if a company is already operating there, unless the company refuses to offer internet speeds the city is seeking.

Pennsylvania was not the first state to restrict municipal broadband, but it “really ignited the monopoly movement to try to prevent cities from building networks,” said Mitchell, of the Institute for Local Self Reliance

Kutztown’s fiber network launched four years before the state law and is grandfathered in. The public broadband provider now serves more than half of the borough’s roughly 2,500 homes.

The biggest challenge of running the network? Competing with the lower prices suddenly offered by a private company once Kutztown launched its network. “When the price war started, it wasn’t as profitable,” Arnold said, noting it took longer to pay off the building cost.

But the whole project was never meant to be a big moneymaker, he added. “It was designed to bring the services to the residents that they needed.”

Staff writer Jonathan Tamari contributed to this report

The Future of Work is produced with support from the William Penn Foundation and the Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Editorial content is created independently of the project’s donors.