Obituary: Kristy Christensen, a pioneering female coal miner

Kristy Ann Christensen: geologist; b January 3, 1985; d February 7, 2022

Kristy Christensen had to get used to working in underground coal mines where she would be told that, if she needed the toilet, she should go and find a quiet place to squat. Rather than turn her off a career, where she could be the only woman working with 1200 men, it left her with a burning desire to improve the way women are treated in mining.

Christensen has died aged 37, after a short battle with breast cancer, leaving behind two young children and a grieving husband, Jamin Christensen, who says he is proud of what she achieved.

“I lost my best friend, an amazing wife, the love of my life and mother of our two beautiful children. The world lost an amazing, caring and passionate person, a warrior for women around the world.”

READ MORE: * The truth about those slaps and more: 15 secrets from Monster-In-Law * 'Secret' coal mining plans on the West Coast alarm Forest & Bird * Pike River mine mother: 'We will not go away' * Solid Energy exec who led Pike River re-entry project new chief mining inspector * Solid Energy proposes the closure of Huntly East mine * Opponents say plan leaves coast unprotected

Christensen achieved worldwide recognition when she appeared on a global 2020 list of the 100 most influential women in the mining industry.

It was a remarkable achievement for a woman who fell in love with rocks as a toddler, and worked hard to become influential in a field long dominated by men.

Her fascinationcame from a grandfather, Keith Cliffe, who had a passion for collecting and polishing rare rocks.

Mum Katherine Jennings recalls that, virtually from the time Kristy could walk, she loved visiting Cliffe, who also had a rock garden.

“She just had a fascination with his rocks, she just felt they were really neat, she was only two or three.”

After graduating from Auckland University with a degree in geology, her first job was prospecting for gold in Waihi.

Along withJamin, a fitter and turner, she moved to Australia in 2008 and began working in mines there.

In a 2020 interview with International Women in Mining, she described what a shock it was to become a Fifo [fly in, fly out] geologist in a coal mine.

“I remember my first time going underground: I was gobsmacked at the scale of the gear, the vehicles, the length of the trip in, the crazy 90-degree turns, and how far in the earth I was. I was also very aware of how much I stood out. I had assumed there would be other females, but I was the only one working underground in a team of 1000, and I was uncomfortable about that.”

Later she would set up a website and company in support of gender equality, Shesfreetobe, which featured graphic descriptions of her life underground.

“When you first start you are assessing the culture and feel of the place so have a lower level of trust in the guys. Out of 1000+ people UG (underground), not everyone is going to be a nice person. It's like in the movies when a woman walks down a dark alley, in the middle of the night, everyone would be yelling don't do it, why would you go in there etc. If it were me in real life walking down that alley, I would have my car keys jammed between my fingers so if someone got me, I would stand a chance with the element of surprise.”

Working in hot and claustrophobic conditions on 12-hour shifts, she faced a major challenge.

“I would bring water … but drinking water means you will need to go. And needing to go presents some real challenges.”

Although there were sometimes “disgusting” underground toilets, she was advised by a supervisor she would be better off to find a quiet spot.

“He advised me that my best bet is to find a quiet place and squat. That seemed reasonable, until I discover that doing this in overalls is a balancing act with all that gear dangling off me.”

In 2020, she wrote that, initially, she had been ready to walk away from the industry because of debilitating headaches, caused by not drinking enough water. She also had to learn to deal with men leaving pornography around to shock her.

Above ground, her problems did not go away. She had to fight for basic facilities like a separate shower, which she insisted on after male miners would offer her a back scrub.

Writing about her experiences, she acknowledged that many women would not have been able to cope. But rather than walking away, she fought for change.

She insisted that women should have appropriate gear (rather than men’s overalls and ill-fitting safety boots) and that their health and safety should be taken seriously.

As she worked her way up thehierarchy, she became influential at a management level and, later at a board level, and was able to bring about change both here and in Australia.

In 2020, she told IWIM that her goal had always been about making the industry more attractive to women, so they did not feel excluded.

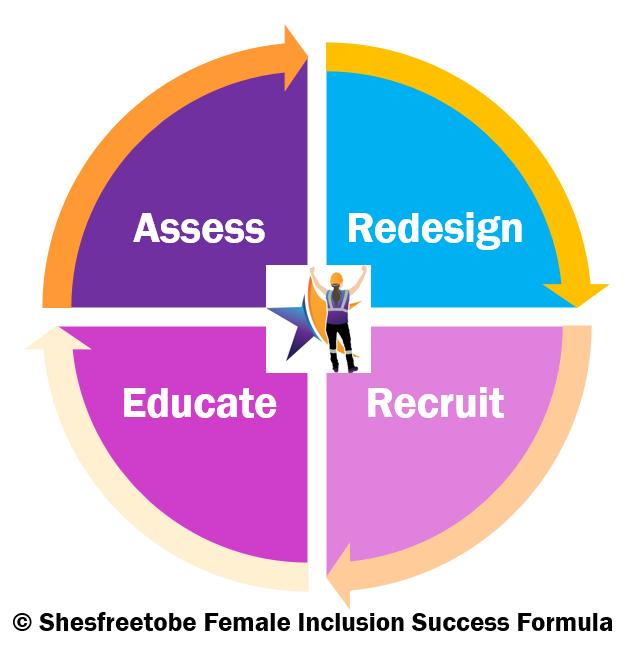

After working in Australia, Christensen returned to New Zealand in 2019, setting up Shesfreetobe.

Promoting herself as a female inclusion expert, she provided expertise to the mining industry on how to get more women involved. Shesfreetobe provided strategies, a toolkit including a shewee (a female urination device), and advice on inclusion.

Despite the bad publicity attached to the mining industry in recent years, she remained committed. She told IWIM that she believed mining should be seen as part of the solution to the problems facing the planet.

“I have an incredible respect for the Earth, its cycles, and that to support our modern lives we need to have balance. Mining provides the building blocks for our green future ... I dream of a day when, instead of seeing mining and environmental challenges as opposed, we can be curious, ask the right questions, and learn from each other to bring our communities together.”

Living in Te Kuiti, she loved gardening and growing vegetables, wanting her children to be close to nature and understand that not everything comes from a supermarket.

Her younger sister, Syke Knox, says she is immensely proud of the hurdles Kristy overcame. It is hard to comprehend how difficult it was for her underground but, rather than walking away, she fought for a better deal, not just for herself but for all women.

The family are staunch Baptists and, growing up, learnt the importance of looking after and accepting everyone in their large community.

Her father, Russell Jennings, regularly took them on long camping trips, where she loved gathering stones. Camping and exploring the back country, is where Kristy gained her independence.

At school, she was very much a “girly girl” who enjoyed ballet, but it was always clear that she would be a miner, due to her love of rocks, says Knox.

Despite having a science-based degree, Christensen did not believe in evolution, and remained a believer in creation.

After her return to New Zealand, she was diagnosed with breast cancer, and had a mastectomy in May 2021. In December, she was told the cancer had spread to her lungs and that it was terminal. She died in February.

Knox says that, although her sister died young, her legacy will be what she did to empower women in a masculine industry.

“That is what she wanted,more inclusiveness and an acceptance that women can do anything.”

Sources: Skye Knox, Jamin Christensen, Katherine Jennings, Shesfreetobe and International Women in Mining.